Solar scientists are predicting the next Solar Minimum, the one we’re entering now, to be long and deep. (Yes, I see the entendres in that wording. Go ahead and get it out of your system. Done? Okay, let us proceed.)

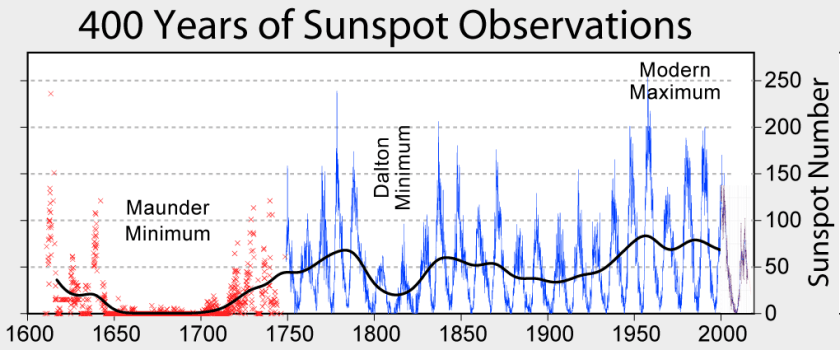

However, I want to note this particular image from the article:

Notice that we had a really low period pretty much over the seventeenth century to the middle eighteenth century. Then we had a dip during the early part of the 19th century, not as low as that Maunder Minimum, but still pretty low. Then things came up from there, and then we had another upswing during the 20th century and we’re finally starting to see a fall off in the 21st.

Note that the end of the Dalton Minimum coincides pretty closely with the end of the Little Ice Age. Yes, solar activity, as measured by sunspot activity, went up before then but climate will tend to lag solar changes because it takes time for the world to warm up once you “turn up the fire” so to speak. Just like if you turn up the heat on your stove, it takes time for the pan to reach full temperature and heavy pans like cast iron skillets take longer than thin, stamped steel or copper.

Now, “Climate change” is getting a lot of press lately. There are a series of questions that need to be asked on the subject of “climate change.”

First: Is the Earth warmer now than it was in times past?

That one’s easy. Of course it is. There have been times where the city I’m writing this in have been under a mile thick sheet of ice. There have also been times when it has been warmer than it is now. There is nothing the least bit controversial about this.

When it comes to more recent times it’s almost as certain. As just one example, the Green Mountain Boys were able to drag captured cannon across the frozen Hudson river on the way to break the siege of Boston. Try doing that now. Yes, it is warmer these days than at the tail end of the Little Ice Age. Few people dispute that.

Second: How much warmer?

This one’s a little harder. For one thing, any measurement has a certain level of uncertainty. Measurement instruments may be off. (Old saying: a man with a watch knows what time it is. A man with two is never sure.) My fever thermometer never agrees with the one at the doctor’s office. And even with the “professional” instrument, they can measure my temperature three times and get three different readings. My blood pressure cuff recognizes this. It measures my blood pressure five times and produces an average.

That’s a complication with even a simple, single measurement of one value taken at one particular location. Now take the entire world, all sorts of different locations from the coldest Antarctic plain to the hottest Libyan desert. Each measurement having some uncertainty. What the “real” average of the “real” temperatures compared to the values you measured, with all their uncertainty, becomes more open to question.

Then add in how much of the Earth you don’t have measurements for. Walk around your neighborhood. How many thermometers do you see whose measurements end up being included in these studies? Any? If there aren’t any then your neighborhood’s temperatures are not being included in the measurements. Given the size of the world there are vast areas that are simply not included in any given set of measurements. IF the unsampled areas are, on average, hotter or colder than the sampled areas, that will be a source of error in the final reult.

This is not to say that measurement is valueless, but one has to remember that a reported value is only an approximation of the “real” value. The “real” value will generally be some value close to the reported value. How close depends on how accurate the individual measurement are, how well the sampling matches the distribution of actual temperatures, and so on. And any reported change in temperature that falls within that error margin is meaningless. It could be no more than that your error fell on one side of “real” this time and fell on the other side the other time.

Third: What is the cause of the temperature rise.

And things get still fuzzier here. The conventional answer is that the rise of industrialization, with the burning of fossil fuels, releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere traps more heat causing temperatures to rise.

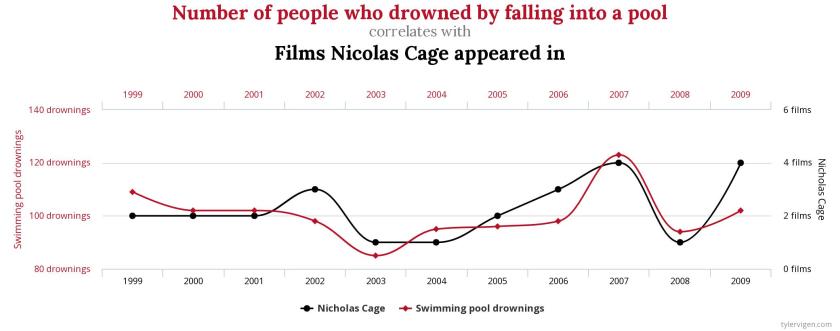

That’s the claim any way. And people can show a correlation, certainly. (Although if you want to look at correlations, go look at that first picture up above.) The problem is that correlation does not, in and of itself, mean causation. If you keep looking, there are all sorts of spurious correlations out there. I especially like this one:

Stop Nick Cage before more people drown!

How do you tell the difference between a spurious correlation and a real causation? Well, the late Richard Feynman gave the answer to that in his lectures, in this case in how to discover a new law of nature. It’s a three step process:

- You guess at what the actual relationship is so that you can express it mathematically. (For instance building a computer model of what you think is happening.)

- You calculate what must happen if your guess is correct. (Running your computer model does this)

- You then compare the results of your calculation to experiment/observation. (Say, you generated a computer model using 20th century temperature and CO2 level numbers, see if what it predicts for the 21st matches what has happened so far. Oh, and just to be safe, run it backwards and see if it retroactively “predicts” what happened in the 19th century. In any case, you must run it against new data, not data that was used to create the model in the first place–that would simply be an exercise in how good your curve fitting was.)

And in the end, if the results of your calculations do not match experiment/observation within measurement error then your guess was wrong. It doesn’t matter how smart you are. It doesn’t matter how “qualified” you are. It doesn’t matter how beautiful your theory is, or how much “sense” it makes, or how “intuitive” it is. It’s wrong.

Fourth, what are the consequences of the temperature rise?

This, I think, is where it breaks down. It seems that “global warming”/”Climate change” has become an excuse for every alarmist to point to every dire thing they can predict.

And it’s always dire things. Nobody ever suggests that, say, longer growing seasons could lead to improved food production or expanded range for tropical and semitropical species–many of which are threatened or endangered because of other reasons.

And they don’t seem to have any restraint. They also don’t seem to let the fact that they’ve been fairly consistently wrong (“ice free arctic by 2013” being one example). If you throw out enough “predictions” of enough different things some will happen by sheer chance.

And if you ignore the cases where you’re wrong? Well, see that bit where Feynman explained how to find a new law of nature.

What mostly happens, though is that something unpleasant happens–a destructive storm, colder than normal weather, hotter than normal weather, excessive rain, drought, pretty much anything “Unusual” (and there’s always something unusual somewhere–the world is a big place)–people point and say “see? Climate change.”

This, my friends, is a classic example of the Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy, where the guy shoots at a wall, then draws the target around where the bullet hit with the bullet hole right in the center then calls everyone over to show them what a great shot he is.

In the end, the “climate change” thing looks a lot like every other set of “environmental doom” predictions dating back to Malthus that have consistently failed to materialize. They remained nothing but the occasional oddity until folk learned that they could use the predictions for political gain, that they could use them to evoke fear sufficient to stampede people into given the doomsayer’s cause greater political power.

It’s a modern day witch hunt, the rousing of the masses in pursuit of heretics, with a new clergy calling themselves “scientists” (while missing that key element of science: if your theory doesn’t match reality, then it’s the theory that’s wrong, not reality). Which, I suppose, makes me a modern day heretic.

Are those torches I smell?